In the early days of Covid, the WSJ published an article about video etiquette that admonished us to, “Maintain professionalism: Don’t let your cats and children walk into the frame.”

It garnered a range of disparaging responses, since it assumed that people had workspaces in their homes that were devoid of children and pets and that they magically had childcare available when none of us were allowed to leave our houses. Why didn’t the original author see that we were all doing the best we could under extremely strained circumstances?

But there was another group of responses that centered on the humanizing aspects of seeing colleagues in their houses, realistically encumbered, with their cats and children climbing on them, and it was this: “Show us all your pets! Introduce us to your children! It’s the only thing that is making this situation bearable!”

The second approach is the one we want to encourage in this post: not merely tolerating your colleagues’ humanity, but embracing it as a way to build connection and trust.

As an entirely remote company, Consensus needs to provide ways to get to know one another artificially, because the conversations in the lunch room and around the water cooler don’t happen unless we make space for them.

The company chat room doesn’t cut it.

To acknowledge this need, we have coffee breaks on the calendar for the whole company, which are scheduled around people’s work days. These are the only meetings that we regularly turn on our cameras, and pets and children are definitely welcome.

(In case you are wondering, the camera isn’t required; it’s just an option. We generally leave our cameras off for work meetings, both for privacy reasons and to reduce distractions on the screen. And at least one of our team members has no camera on their computer at all.)

What do we lose when we go remote?

No matter how abstracted or technical our work becomes, we are still social creatures who rely upon reading one another’s faces and body language to know what’s happening in a conversation. When things go wrong in projects (even in projects that seem to be purely technical), it almost always comes down to questions of trust and communication.

Regardless of how “meta” some people may want us to get, we still live in bodies in the physical world.

When we go remote (especially by accident), we can be reduced to communicating through text or formal meetings. The stresses on conferencing systems and people’s home WiFi left a lot of people meeting purely by voice for the last year. And a lot of large companies (for good reasons) confined people’s communication to formal channels that could be monitored for inappropriate use.

Unfortunately, the glue that binds a company together is informal communication: Gossip, if you must.

We need to know what’s happening in people’s lives to make sense of what is happening in their days. If, for example, they are always required to pick up their children at 4PM, but we’re not allowed to know about that, all we see is that they keep disappearing for an hour in the afternoon. In the absence of information about people we don’t trust, we make up stories. (They’re often not very charitable.)

Projects run on trust

Trust is not something that is given. It’s earned.

For a project to succeed, there are some essential things that have to be true, that we also have to believe about one another.

Most basically, the people working together have to honestly represent their skills, their progress, and their effort. Things go very wrong indeed when people start covering up challenges and failures or overpromising and underdelivering.

At a higher level, we also have to trust that everybody on the project has a good outcome in mind. Ideally, there should be a clear overlap in those visions so that we are also working towards the same good outcome. Still more importantly, that outcome should benefit everybody on the team.

We have probably all worked with people who didn’t meet these basic requirements of trust-worthiness… they were in it for themselves, they were actively undermining their coworkers, or they were in over their heads but were too embarrassed to admit it.

But most of the places where it breaks down come down to “not knowing one another well enough.”

This is a high risk for remote companies, and has been a huge focus of the debate about the Return to the Office: employers don’t trust their employees, and they haven’t come up with ways to bridge that gap other than through monitoring - which is what you use in a low-trust environment. It’s not an appropriate way to form and encourage high-performing teams.

Remote on purpose

In the “when are you going back to the office” conversation, we’ve been left out. Like more and more digital companies, we never had an office to go to in the first place. But that doesn’t change the fundamentally social characteristics of trust.

I want to point out some of the advantages of the remote workplace in getting to know one another.

The blending of our work and home selves can have some significant boundary problems if we’re not careful. (9 pm text messages are right out.) But it can mean that we’re not covering things up in the same way.

When one of our children is home sick, we all know about it. For that matter, when somebody’s babysitting falls through or they have to go to an appointment in the middle of the day, it’s much easier to say, “I’m not available,” when everybody understands more of the reality they are navigating.

We recently had a long-delayed company retreat, and it was a bit odd to realize (as we walked up to one another in person)… that most of us had never actually “met” before. We know one another’s kids’ names and pets, and what kind of work their spouses do, what renovations are going on in their houses. We’ve seen the backdrops and piecemeal workspaces they resort to as they share the WiFi with varying numbers of family members.

We’ve been “in” one another’s yards, and dining rooms, and hallways, and we’ve shared our various approaches to making coffee and the views out our windows in the middle of storms. (Generally with a caution that we may lose power at any moment.) We “know” one another in a way that we haven’t necessarily known our in-person colleagues in the past.

A lot of the rhetoric around virtual spaces is that the relationships we form there aren’t “real.” To a certain extent, as long as they are mediated and kept artificially distant, that can be true. But if you want to build a cohesive remote team, you need to work around the limitations of the medium.

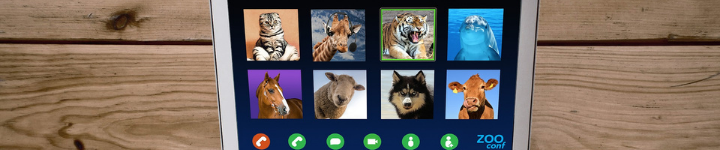

It can be as simple as introducing your cats to one another.

The article Remote Connections: Show Us All Your Pets! first appeared on the Consensus Enterprises blog.

We've disabled blog comments to prevent spam, but if you have questions or comments about this post, get in touch!